Programming Languages and Multicore Crisis

For a couple of years ago we have witnessed the rise of programming languages different from conventional imperative paradigm (C/C++, Java, C#, PHP, etc..), such as Erlang, Elixir, Scala, etc. The question is why?

History

To explain why this phenomenon is happening and why it’s getting stronger, we have to refer to the history first. Something happened in 2002, something that changed the way that Microprocessors were being designed and built. Over the last 20 years, chips were being getting bigger and the clock frequency getting faster, until in 2002 they reached the limits of Hardware: “you could not reach the entire chip in one clock cycle”. This meant a catastrophe for the Hardware, because it meant stop scaling.

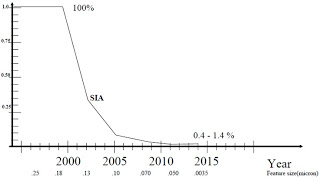

Figure 1: Fraction of Chip reachable in one clock cycle [7].

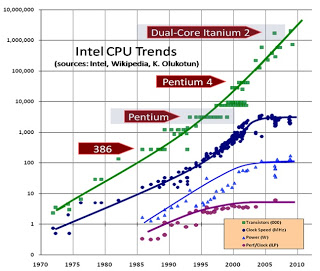

In Figure 1 we can observe how from 2000 comes an exponential drop in the percentage of chip reachable in one clock cycle per year. Now let’s review what has happened over the last 25 years. In Figure 2, the green curve shows how chips had became getting bigger and bigger, significantly increasing the number of transistors. On the other hand we see the logarithmic trend of clock speed (blue curve), power (light blue curve) and performance per clock cycle (purple curve), and clearly shows how these variables have gone fading. In conclusion, we see that the vertical scalability of chips had reached its limit, and the graph shows the turning point in the year 2002.

"...Electronic circuits are ultimately limited in their speed of operation by the speed of light... and many of the circuits were already operating in the nanosecond range.".

[Bouknight et al., The Illiac IV System. 1972] [1]

Figure 2: Intel CPU trends (2009).

"...for the first time in history, no one is building a much faster sequential processor. If you want your program to run significantly faster, say, to justify the addition of new features, you’re going to have to parallelize your program.".

[Ref. 1. Patterson y Hennessy]

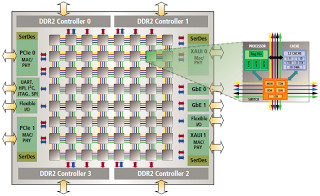

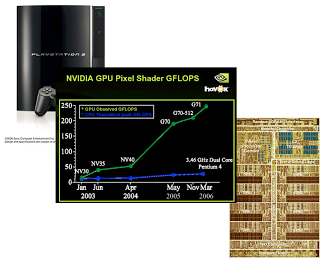

Since 2005 nobody builds faster sequential Microprocessors. The paradigm of computing architectures has shifted to multiple CPU architectures (Multicore/Multiprocessors architectures). Figure 3 and Figure 4 are examples of the types of hardware architectures that we see today.

Figure 3: Tile64 architecture [8].

Figure 4: PlayStation3 Cell Processors, Multi GPUs Architectures.

But what has it to do with programming languages? Simply that, when hardware (computer architectures) begins to change, programming languages begins to change as well –since they are closely related. Programming languages hadn’t changed over the past 25 years because hardware architectures hadn’t changed over the last 25 years –there wasn’t pressure. But from 2005 all this changed radically.

¿How much does it hurt? Surely wasting two cores doesn’t hurt, 4 cores will hurt a little, 8 cores hurts a little bit more, 16 cores and starts to hurt, 32 cores hurts a lot (Intel “Keifer” project: 32 cores 2009/2012 [9]), 1M cores “ouch” (2019, complete paradigm shift) [4] [6]. Hardware paradigm has shifted into concurrency and/or parallelism, therefore, Software should do it too. A new paradigm called “Concurrency-Oriented Programming” then arises [Ref 4. Joe Armstrong].

Mutable State and Concurrency

¿Why programming languages like Java, C, C++, C#, etc.., don’t fit well in these new computing architectures? Well this is due to several factors, but let’s start talking about two that might be the most relevant: mutable state and concurrency.

"How can we write programs that run faster on a multicore CPU? It’s all about mutable state and concurrency.".

[Ref 4. Joe Armstrong]

First, let’s mention the known concurrency models today:

- Traditional Multithreading

- OS Threads

- Shared memory, locks, etc.

- Async or Evented I/O

- I/O loop + callback chains

- Shared memory, futures

- Actor Model

- Shared nothing "processes"

- Built-in messaging

For example, Erlang, Oz, Occam and more recently Scala, chose “Message Passing” (Actor Model [5]), all others as: Java, C, C++, C#, Ruby, Python, PHP, Perl, etc., they went by the model of “Shared Memory” (Traditional Multithreading and/or Async I/O).

In the message passing model, shared state doesn’t exist. All computations are performed within the process, and the only way to exchange data is through asynchronous message passing. But why is this good?

"Shared state concurrency involves the idea of “mutable state” (literally memory that can be changed)—all languages such as C, Java, C++, and so on, have the notion that there is this stuff called “state” and that we can change it. This is fine as long as you have only one process doing the changing. If you have multiple processes sharing and modifying the same memory, you have a recipe for disaster—madness lies here..

[Ref 4. Joe Armstrong]

Normally to prevent simultaneous modifications we use shared memory locking mechanisms, also known as Mutex, synchronized methods, etc., But at the end, locks.

Scenario 1: If a program fails in the critical section (when you get the lock), it is a disaster. The other programs do not know what to do, do not realize what happened and therefore there is no way that you can recover, might just wait indefinitely for the lock, because as the program that acquired first died, there will be no one who releases it. Scenario 2: If a program corrupts memory in the shared state, a disaster too. As in the previous scenario, the other programs do not know what to do, they do not realize what happened and therefore there is no way that you can recover either. Now, ¿how do programmers to solve these problems? With great difficulty surely. Shared memory is the hard way. Fault tolerance is difficult to achieve with shared memory –sharing is the property that prevents fault tolerance.

Programming on multicore architectures is difficult because of the shared mutable state. In functional programming languages shared-mutable-state don’t exist. Languages like Erlang and Scala have the intrinsic properties to program on multicore computers –concurrency is mapped into multiple CPUs, no mutability means that we have no memory corruption problems.

Pieter Hintjens, iMatix’s CEO (company behind ZeroMQ) gives the next concurrency law:

Hintjens’ Law of Concurrency

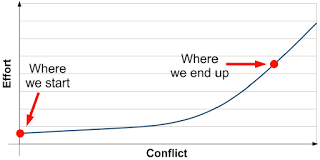

E = MC2

E is effort, the pain that it takes

M is mass, the size of the code

C is conflict, when C threads collide

This means that as more threads are sharing memory, the effort to achieve concurrency increases exponentially (in power of 2), which of course degrade performance equally. See Figure 5.

Figure 5: Hintjens' Law of Concurrency: E = MC2 [12].

Now, with ZeroMQ equation works but C is constant: E = MC2, for C = 1 (Figure 6). ZeroMQ is a toolkit (library) for communicating through message passing, made for concurrency and distributed systems. ZeroMQ provides bindings for different languages like C, C++, Java, Python, Ruby, PHP, Scala, Erlang, etc., which makes easier the construction of concurrent applications, oriented to message passing, on almost any platform and/or programming language. It is another alternative that definitely worth exploring.

Figura 6: Ley de concurrencia de Hintjens: E = MC2, para C = 1 [12].

Erlang in native way (implements actor model in native way), and Scala with Akka (actor model is optional in Scala), follow the same behavior in Figure 6, E = MC2 for C = 1, because they use message passing and run under the premise of “shared nothing”.

Impedance Mismatch

A little quote first:

"The world is concurrent but we program in sequential languages".

[Ref 4. Joe Armstrong]

There is an impedance when we try to program parallel and/or concurrent applications with sequential programming languages (imperative paradigm), since these languages don’t fit naturally with parallelism/concurrency oriented paradigms, they don’t fit naturally into multicore/multiprocessor architectures. Build programs with high degree of parallelism and/or concurrency, distributed, fault-tolerant, etc.., is artificially complex with sequential programming languages –they add an artificial complexity [4] [6].

Sequential programming languages (imperative paradigm) don’t model reality, which is multiprocessor and/or multicore architectures. Many of them were designed over 15 years ago, when the trend of Microelectronics was build larger and faster processors to execute sequential logic. But as I have been repeating, the focus shifted radically, thus programming languages should do so too.

Some Examples

Let’s see with some examples what artificial and/or accidental complexity means.

"Programming consists of overcoming two things: accidental difficulties, things which are difficult because you happen to be using inadequate programming tools, and things which are actually difficult, which no programming tool or language is going to solve.".

Joel Spolsky reviewing Beyond Java

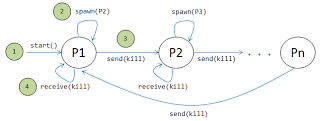

Exercise 1: you have probably heard about this problem: “The deadly ring of processes (or threads).”. The parent spawns a child and sends a message to it. Upon being spawned, the child creates a new process and waits for a message from its parent. Upon receiving the message, it terminates normally. The child’s child creates yet another process, resulting in hundreds, thousands, and even millions of processes. The last child kills the parent, the first parent. In the Figure 7, we can see how it works. Now comes the challenge, solve the problem in Java, C, C++, C#, Python, Ruby, PHP, etc., any imperative language paradigm (sequential).

Figure 7: Deadly ring of processes/threads.

This is a sequential benchmark that will barely take advantage of SMP on a multicore system, because at any one time, only a couple of processes will be executing in parallel. What we will be able to see, is the overhead to create and kill threads, depending on the chosen programming language to develop the problem. However, for our purpose this is useful, because the idea is to show the complexity that exists to build a simple program like this –which involves threads/processes and communication between them– with a language from imperative paradigm (Java, C, C++, C# etc.).

The program involves thread management and communication between them. For communication we can use shared memory or message passing. If we use shared memory, we have to use synchronization mechanisms (locks). In languages like Java, C#, C or C++, if we want to use message passing, certainly touches us deal with sockets, pipes or other mechanisms of IPC (Inter Process Communication). Either case, an imperative language paradigm is quite tedious and complicated to solve the problem. Now let’s see the solution with a concurrency-oriented language (Concurrency-Oriented Programming [Ref. 4. Joe Armstrong]) as Erlang:

-module(process_ring).

-export([start/1, start_proc/2]).

start(Num) ->

start_proc(Num, self()).

start_proc(0, Pid) ->

Pid ! ok;

start_proc(Num, Pid) ->

NPid = spawn(?MODULE, start_proc, [Num-1, Pid]),

NPid ! ok,

receive ok -> ok end.Let’s take a look at the execution of the program, initially with 100,000 processes, after 1,000,000, and then finally with 10,000,000 of processes. Erlang’s function timer:tc/3 was used to calculate the time it takes the program to run, and in response yields a tuple of two elements {Time, Value}, the first is the time in microseconds and the second is a return value by the execution (in this case ok).

1> c(process_ring).

{ok,process_ring}

2> timer:tc(process_ring, start, [100000]).

{484000,ok}

3> timer:tc(process_ring, start, [1000000]).

{4289360,ok}

4> timer:tc(process_ring, start, [1000000]).

{40572800,ok}In Erlang we just needed 10 lines of code to solve the problem. The purpose here is to point out that there is a large family of abstractions that can be easily constructed from the basic language primitives: spawn, send and receive (!). These primitives can be used to create our own parallel control abstractions in order to increase the concurrency of the programs. I won’t discuss and/or explain in detail the program, because it is not the purpose of reading to understand the lexical, syntactic and semantic rules of Erlang, we leave that for the next time.

This example clearly shows how easy and natural is to build a concurrency-oriented program with a language like Erlang, which implements actor model [5], messaging is incorporated natively in the language as the functions for handling local and distributed concurrency.

"... To me Erlang/OTP is the type of system my middleware colleagues and I spent years trying to create. It’s got so many things a distributed systems developer wants: easy access to networking, libraries and utilities to make interacting with distributed nodes straightforward, wonderful concurrency support, all the upgrading and reliability capabilities, and the Erlang language itself is sort of a “distributed systems DSL” where its elegance and small size make it easy to learn and easy to use to quickly become productive building distributed applications.".

[Ref. 10. Steve Vinoski].

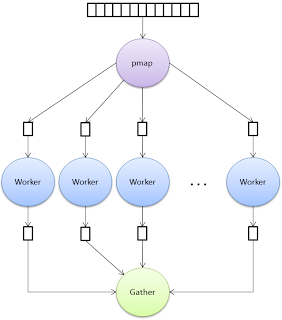

Exercise 2 : Let’s implement something that might seem a bit more complicated. In many programming languages there is a high order function named map whose functionality is to apply a given function on each element of a list, the function takes as input a list of items and a function that is going to be applied to each element. Well, now we’re going to implement the parallel version of this function: pmap, that receives the same parameters of the map version. The pmap must create a thread/process per each element in the list, so each of them will be in charge of one element to apply the function. Then pmap should gather the result delivered by each thread/process. Each thread/process must send the result using messaging. Figure 8 shows how pmap works, and then the solution in Erlang .

Figure 8: Parallel version of "map" ("pmap").

Simple solution of “pmap” in Erlang:

-module(pmap).

-export([map/2, pmap/2, gather/1, do_f/3]).

%% Original map function

map(F, L) ->

[F(X) || X <- L].

pmap(F, L) ->

gather(spawn_jobs(F, L)).

spawn_jobs(F, L) ->

Parent = self(),

[spawn(?MODULE, do_f, [Parent, F, I]) || I <- L].

do_f(Parent, F, I) ->

Parent ! {self(), (catch F(I))}.

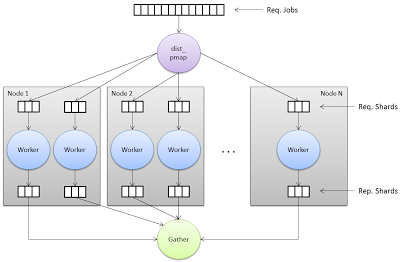

gather(Pids) ->

[receive {Pid, Res} -> Res end || Pid <- Pids].We could further complicate the exercise. Another version of pmap wouldn’t only distribute the work in local processes on a multicore CPU, but also on multiple nodes in a distributed network. In this case, we will have a new version: pmap_dist. This function must split the jobs using any heuristic and distribute the pieces (smaller portions of jobs) in workers (processes) running on multiple nodes in a network (including the node where you initially executed pmap_dist). Then wait to gather all processed pieces to assemble the final result –workers send their results to the parent process. See Figure 9.

Figure 9: Distributed version of "pmap" (pmap_dist).

This time I won’t show how to implement this distributed version. I’ll just say that in Erlang is a matter of adding a few lines more to the code. It is a challenge, and even more in a language like Java, C, C++, C#, etc. . –just try it!

Multithread Models

Now we will do a lower level analysis, we’ll be in Hardware and OS (Operating System) level. Why? Well, performance and scalability of software architectures on multicore Microprocessors depends on the process/thread model implemented by the OS.

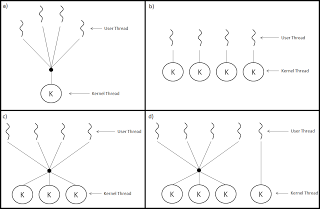

Multi-Thread support may be provided either at the User or Kernel level. User threads are supported above the kernel and are managed without kernel support, whereas kernel threads are supported and managed directly by the operating system. Virtually all contemporary operating systems-including Wiridows XP, Linux, Mac OS X, Solaris, and Tru64 UNIX (formerly Digital UNIX)-support kernel threads. Ultimately, a relationship must exist between user threads and kernel threads. In this section, we look at three common ways of establishing such a relationship [2]. Let’s going to review quickly the three more common ways to establish this relationship.

Figure 10. a) Many to One model. b) One to One model. c) Many to Many model. d) Two-level model. [Ref. 2. Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne].

The many-to-one model (Figure 10.a) maps many user-level threads to one kernel thread. Thread management is done by the thread library in user space, so it is efficient; but the entire process will block if a thread makes a blocking system call. Also, because only one thread can access the kernel at a time, multiple threads are unable to run in parallel on multiprocessors [2]. This approach is used by many virtual machines, where these threads are known as “Green Threads”, threads that are scheduled by a virtual machine (VM) instead of natively by the underlying operating system. Green threads emulate multithreaded environments without relying on any native OS capabilities, and they are managed in user space instead of kernel space, enabling them to work in environments that do not have native thread support. Some examples: Java 1.1, Ruby before 1.9 version, CPython with Greenlets, Go, Haskell, Smalltalk, etc. [11].

The one-to-one model (Figure 10.b) maps each user thread to a kernel thread. It provides more concurrency than the many-to-one model by allowing another thread to run when a thread makes a blocking system call; it also allows multiple threads to run in parallel on multiprocessors. The only drawback to this model is that creating a user thread requires creating the corresponding kernel thread. Because the overhead of creating kernel threads can burden the performance of an application, most implementations of this model restrict the number of threads supported by the system. Linux, along with the family of Windows operating systems, implement the one-to-one model [2].

The many-to-many model (Figure 10.c) multiplexes many user-level threads to a smaller or equal number of kernel threads. The number of kernel threads may be specific to either a particular application or a particular machine (an application may be allocated more kernel threads on a multiprocessor than on a uniprocessor). Whereas the many-to-one model allows the developer to create as many user threads as she wishes, true concurrency is not gained because the kernel can schedule only one thread at a time. The one-to-one model allows for greater concurrency, but the developer has to be careful not to create too many threads within an application (and in some instances may be limited in the number of threads she can create). The many-to-many model suffers from neither of these shortcomings: developers can create as many user threads as necessary, and the corresponding kernel threads can run in parallel on a multiprocessor. Also, when a thread performs a blocking system call, the kernel can schedule another thread for execution [2].

One popular variation on the many-to-many model still multiplexes many user-level threads to a smaller or equal number of kernel threads but also allows a user-level thread to be bound to a kernel thread. This variation, sometimes referred to as the two-level model (Figure 13.d), is supported by operating systems such as IRlX, HP-UX, and Tru64 UNIX. The Solaris operating system supported the two-level model in versions older than Solaris 9. However, beginning with Solaris 9, this system uses the one-to-one model [2].

The OS provides an API for creating and managing threads. There are two primary ways of implementing a thread library. The first approach is to implement a library entirely in user space, without kernel support. All code and data structures for the library exist in user space. This means that invoking a function in the library results in a local function call in user space and not a system call. The second approach is to implement a kernel-level library supported directly by the operating system. In this case, code and data structures for the library exist in kernel space. Invoking a function in the API for the library typically results in a system call to the kernel [2].

Three main thread libraries are in use today: (1) POSIX Pthreads, (2) Win32, and (3) Java. Pthreads, the threads extension of the POSIX standard, may be provided as either a user- or kernel-level library. The Win32 thread library is a kernel-level library available on Windows systems. The Java thread API allows threads to be created and managed directly in Java programs. However, because in most instances the JVM is running on top of a host operating system, the Java thread API is generally implemented using a thread library available on the host system. This means that on Windows systems, Java threads are typically implemented using the Win32 API; UNIX and Linux systems often use Pthreads [2].

In Java, C#, recent versions of Ruby, Python, etc., Multi-Thread implementation is through the host OS library, and here is where the heart of the matter resides. For Windows and Linux, which are practically the most common/used operating systems today, the threading model is “One to One”, their thread libraries are Win32 and Pthreads (POSIX), which are implemented in kernel space. The problem is that the number of kernel threads is limited, you could only climb a few thousand; clearly this also depends on the number of processors and/or cores that the hardware provides. ¿What happens in applications or systems with massive concurrency? Under this model, ¿can we scale to millions of threads? Perhaps surely a supplier will come to tell us: to scale at that level what we need is hundreds of processors and/or cores, in other words, solve the shortcomings of the Software with Hardware, quite common today. Sometimes it’s just a matter of optimizing the use of resources, in this way we could, with the same hardware, reach out the desired concurrency level. We often wasted resources, since in most of the cases we create kernel threads to run trivial tasks.

Let’s imagine you have a typical multilayer system (Figure 11). A user interacts with the browser, the browser talks to the server and the server that talks to the database. Let’s focus on the server, but the problem happens equal or similar way to the database layer. On the server side, we have the classic model for handling sessions, each session is represented by a thread, and the main task of this thread is go to read/write to the database. If we assign to each session a kernel thread, we are limited in the number of concurrent sessions, depending on the OS and number of processors and/or cores that we have. If the traffic on our website is considerably high, to the point of requiring more concurrent sessions than the available kernel threads of the machine(s), we have a serious problem. Immediate and easy solution (we’ll call to this solution “vendor oriented solution”): “more machines (increase Hardware).” Sounds familiar isn’t?

Figure 11: Typical multi-layer system.

But what would happen if a kernel thread could handle all traffic and load generated by N concurrent sessions? Surely we would optimize in large percentage the utilization of our resources, and we could tell the supplier in most cases we don’t need so many machines or processors as he thought, because with this approach we need less hardware resources to perform the same task, it is just a matter of tuning our software in order to get the max profit from our Hardware. This will result in an easy or extremely difficult task, depending on the tools, platforms and programming languages that are chosen to build the system.

I’m going to do a break here. Note that if we had an OS that implements a “Many to Many” threading model, we wouldn’t have this problem, since you can tune the OS with a limited number of kernel threads, proportional to the number of processors and/or cores, and our web application could assign user threads per session (or Green threads), so that we can have a much larger number of user threads (sessions) than kernel threads, thus increase the capacity to serve more concurrent sessions without increase our infrastructure or hardware resources. The point is, this model is supported just by a few operating systems, and those few, in most of the cases are privates, which is a big problem if we are talking about of hundreds, thousands or even millions of processors and/or cores, since the cost of the licensing is proportional to the number of them. In addition, the most commonly used operative systems in business environments are Linux and Windows, and their multithread model is “One to One”.

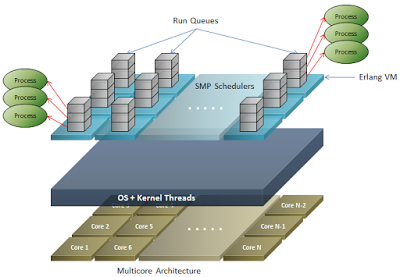

What we need is a platform above the OS, that abstracts the implementation of processes and threads of this, allowing that scale-out on multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures be agnostic from OS. The most notable example of this is the implementation of the Erlang VM, which internally has a sort of guest OS that implements a multithread model of “many to many”. The guest OS when the Erlang VM starts, spawns a “Scheduler” per each available core, and this is executed on a kernel thread; this is what is known as “SMP Schedulers” (Symmetric Multiprocessing Schedulers). To each scheduler is assigned an execution queue (Run Queue) to which is assigned a certain number of processes. When a process is created in Erlang through the spawn function, a LWP (Light-weight process) is created, which are “Erlang Green Threads”, and this is assigned to a run queue. Processes are distributed evenly over the several schedulers, therefore, implicitly being distributed over cores, as there are N schedulers for each N cores, each scheduler runs in a thread kernel, kernel threads are managed by the host OS, and this in turn distributes them evenly over the cores. Figure 12 shows a view of the process model of Erlang VM.

Figure 12: Erlang VM: process model.

By examining different programming languages and their implementations, you can clearly see why Erlang is different, it is more than a programming language, is a whole platform (Erlang/OTP) for the development of distributed applications, fault-tolerant, highly concurrent and available, etc.

Therefore, is important to note that is not only the language, if it is functional, object oriented, imperative, declarative, etc., but also in the case of interpreted languages (dependent on a virtual machine), the implementation of the virtual machine and/or guest OS, since from it depends scalability over the multicore architectures and/or multiprocessor.

Conclusions

As a first conclusion, because computing architectures began to change since 2002, programming languages should do it too, since they are directly related each other. We need languages that fit well with the reality of multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures, to enable easy building of concurrent applications, also enable to easily scale to desired levels, exploiting Hardware at 100%. The most relevant cases that fits with this evolution and revolution of multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures are: Erlang/Elixir, Scala/Akka and ZeroMQ –the latter with additional effort, since it is just a library for message passing and concurrency, not a language and/or platform as if they are the first two.

Moreover, to make the software fit naturally in these multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures, we need certain features on our Software. The first and most important is “mutable state and concurrency”. The idea is to prevent the sharing and/or mutable state, as this makes difficult to develop on multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures, oriented to parallelism (Thread Level Parallelism [1]), this is the property that prevents scaling and fault tolerance. For communication, use message passing, shared-nothing (taking as reference the actor model [5]). Second, the model of processes and threads, this refers to the way you create and manage threads and/or processes within the host OS and the guest OS. From the way that the host and guest operative systems implements the multithreading model respectively, depends scalability over multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures. Now, the guest OS can implement its multithreaded model either using the threads library provided by the host OS directly (JVM , Ruby , Python, etc.), or creating a layer that abstracts the multithreading model of the host OS and enable an API for handling user-level threads or “Green threads” (Erlang). Finally, we might mention “Impedance Mismatch”, which refers to the incompatibility of models: sequential programming languages vs multicore and/or multiprocessor architectures, oriented to parallelism. This property is what causes accidental complexity, which refers to things that are difficult or complicated due to the use of inappropriate tools or language. In this case, developing concurrent, distributed and fault-tolerant applications, is extremely difficult due to languages like Java, C#, C , C++ , Ruby, etc., since they are inappropriate for develop this kind of applications with these properties, much effort is required to achieve these properties, and often is not possible to reach the expected levels.

As a final thought, I would like to emphasize that the way what we’ve been developing applications is changing dramatically, therefore, it is important to begin studying multicore and/or multiprocessor computing architectures, along with languages, platforms, tools, etc.., which allow to make appropriate use of them. The paradigm has shifted from programming sequential logic to programming parallel logic, today we talk about a concurrency oriented paradigm [4].

References

- Computer Architecture, A Quantitative Approach – 4th Edition. David Patterson and John Hennessy.

- Operating System Concepts – 8th Edition. Abraham Silberschatz, Peter Baer Galvin and Greg Gagne.

- Distributed Systems, Principles and Paradigms – 2nd Edition. Andrew S.Tanenbaum and Maarten Van Steen.

- Programming Erlang, Software for a Concurrent World – 2007. Joe Armstrong.

- Actor Model of Computation: Scalable Robust Information Systems. Carl Hewitt. 2012.

- erlang-software-for-a-concurrent-world

- ErikH-intro.pdf

- PB010_TILE64_Processor_A_v4.pdf

- project-keifer-32-core

- an-interview-with-steve-vinoski-stevevinoski

- Green_threads

- 0MQ presentation